When a story won't let you go

Reporting on a nickel refinery in Lawton Oklahoma, staying connected to the community and finding my rhythm as a journalist while facing ADHD and Bipolar disorder head on.

The first time I drove into Lawton, Oklahoma, in December 2023, the Wichita Mountains caught me off guard, chills running up my spine. I’d heard about them, but I didn’t expect them to rise so suddenly from the flat southern plains.

That evening, the sky burned in streaks of tangerine and fuchsia, stretching endlessly over the horizon. It was strangely warm for late fall. I was on my way to a town hall meeting where Westwin Elements, a startup metals refining company, would face the community four months after breaking ground on a new nickel refinery.

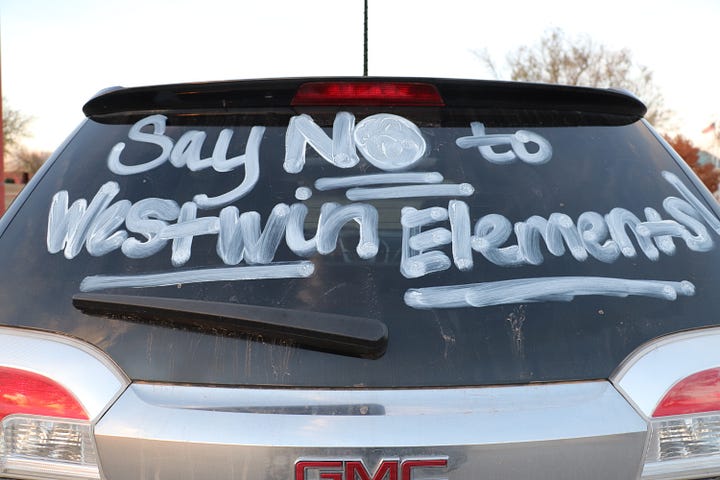

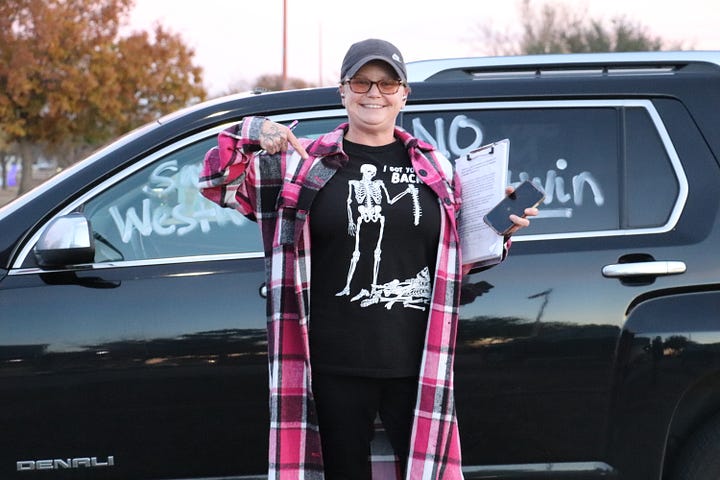

By the time I arrived, the tension was undeniable. Protesters had spray-painted their cars in defiance, urging others to sign a petition against the refinery.

Their frustration was raw—fueled by fears of contaminated land, polluted air, and a history of industries exploiting Indigenous land under the guise of progress.

This was a story worth telling. But was I the one meant to tell it?

Losing my job, losing my confidence, sticking to the story

As I reported on Westwin, my own foundation was crumbling.

Strike one: I wrote about hip-hop and mental health instead of oil and gas—topics my editor deemed more important. He buried my work, ignored my calls, and eventually stopped responding altogether.

Strike two: Under pressure, I made a mistake. Instead of building my own sources, I relied on another outlet’s reporting. I didn’t realize how serious that was—until it became a weapon used against me.

For three months, I became a ghost in the newsroom. Colleagues avoided me. My work sat unpublished. Instead of mentorship, I got a performance improvement plan — a slow, abusive, silent push toward the exit.

No guidance. No way forward. Just isolation. I poured everything into proving I belonged, but no matter how hard I worked, I was never accepted.

In those three months, I attended Comanche Nation business council meetings, Westwin Resistance’s first organized protest where I connected with Kiowa and Absentee Shawnee leader of the resistance, Kaysa Whitley.

Eventually, I left the newsroom. Imposter syndrome settled in as searched for new ways to make money, places to platform these stories, relearning the life of a freelancer. I could no longer afford to visit Lawton, but still kept in touch with Kaysa and other community members.

Without journalism, I felt unmoored. It had been my anchor — my ikigai, my purpose. Now, I questioned everything. Was I even still a journalist? Did I deserve to be? Could I take on a story as complex and urgent as this?

Imposter syndrome hit fast, thick as wet concrete in the summer heat. Every interview felt like a test I was bound to fail. Was I asking the right questions? Finding the right voices? Doing enough?

Still, something pulled me back—the community. Even when I wasn’t writing, I was thinking about the Comanche elders fearing for their ancestors’ graves, the scientist warning of toxic gas, the activists risking arrest just to be heard.

I didn’t feel confident in myself. But I knew their voices mattered. So I continued to show up

Mental health & the reporting process

For years, I had struggled with focus, deadlines, and the crushing weight of perfectionism. Untreated ADHD and bipolar disorder made my energy unpredictable — hyper-focused one moment, paralyzed the next. Losing my job magnified everything.

So, as I investigated the environmental risks of nickel refining, I was also navigating my own mental landscape — starting therapy, beginning medication, finally confronting the chaos inside my mind.

Just as Westwin was being scrutinized for its impact on Lawton, I was learning to interrogate my own patterns. Both needed accountability.

What this story taught me about journalism

One of the biggest lessons I learned: journalism isn’t just about research. It’s about being there.

I spoke with Indigenous leaders, environmental scientists, and activists. I pressed Westwin’s investors for answers, even when their reassurances felt hollow. I didn’t just cover what was happening—I worked to understand what it meant for the people breathing this air, living on this land, carrying this history.

And that’s when I remembered why I became a journalist in the first place. To amplify voices often ignored. To ensure history doesn’t repeat itself unchecked.

Finding my way back to journalism

Nearly a year passed before I published my first piece on Westwin. By then, something had shifted.

I was still uncertain about my career. Still navigating my mental health. Still learning to trust my voice. But this time, I didn’t feel like an outsider in my own profession.

I had reported the story the way it needed to be told—through the voices that mattered most.

Journalism, I realized, isn’t about having all the answers. It’s about asking the right questions, showing up, and staying with the story even when it’s hard.

For the people of Lawton, the fight isn’t over. And for me, neither is the work.

Final reflection

Driving back through Oklahoma, past the Wichita Mountains, the sky once again blazes in pink and gold.

This time, I don’t just see a beautiful sunset—I see a reminder.

A reminder that stories take time. That truth isn’t always simple. That my voice, despite the doubt, belongs here.

And maybe, just maybe, I am exactly where I’m supposed to be.

Check out the full story at The Black Wall Street Times and follow for more.

Damn B this is good stuff (also unfortunate in some ways) and your processing altogether is reflective and catalytic. You’re someone whose stories I will be reading for the rest of my fleshy existence

Ty for continuing to share our story! 💜